New research from James Locke's group shows that clocks in plant seedlings can self-organise without a master.

From cyanobacteria to humans, nearly all living things on Earth have an internal circadian clock that regulates their activities on a 24-hour cycle. For mammals, there is a master clock located in the brain that controls peripheral clocks elsewhere in the body; plants also have multiple clocks, but it has been unclear whether they have a brain-like master that coordinates them.

From cyanobacteria to humans, nearly all living things on Earth have an internal circadian clock that regulates their activities on a 24-hour cycle. For mammals, there is a master clock located in the brain that controls peripheral clocks elsewhere in the body; plants also have multiple clocks, but it has been unclear whether they have a brain-like master that coordinates them.

New research published today in the open-access journal PLOS Biology, led by James Locke’s team in the Sainsbury Laboratory at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with the University of Liverpool and the Earlham Institute, shows that clocks in plant seedlings can self-organise without a master, collecting external signals such as light and temperature, and then communicating this information with their neighbours.

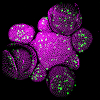

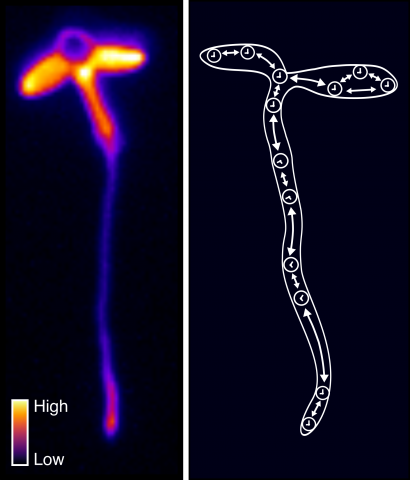

“By analysing all the major organs together, we can see how their different clocks interact, helping us to understand how plants coordinate their timing,” says lead-author Mark Greenwood. “We found that in thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) seedlings, the clock runs at different speeds in each organ with as much as four hours’ difference in period between the fastest and slowest clocks.”

While the individual clocks in organs have different speeds (periods), the research team discovered that this didn’t result in chaos. “Although the clocks’ speed is set locally by their organ-specific inputs such as light, they are also talking to their neighbours to locally coordinate themselves. This combination of period differences between organs and local cell-to-cell signals produces spatial waves of clock gene activity (see time-lapse movie below). This means that plant clocks are set locally, but coordinated globally via spatial waves,” Greenwood says.

Read More: Plants can tell time even without a brain

Research group leader, Dr Locke says understanding how plant circadian clocks work may help to improve crop productivity. “Plant circadian clocks help to time many processes that are important for agriculture, including growth, flowering, and resistance to disease. Understanding how the clock is coordinated should in the future allow us to manipulate how plants anticipate daily events in order to boost crop yield."

Citation

Greenwood M, Domijan M, Gould PD, Hall AJW, Locke JCW (2019) Coordinated circadian timing through the integration of local inputs in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol 17(8): e3000407. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000407

Funding

This research was supported by the Gatsby Charitable Foundation and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC)