Cambridge Festival 2025

Build your own mini-genome

At the Sainsbury Laboratory in Cambridge, we combine experimental research with computer models to study how plants evolve. Our computer models simulate evolution at a faster pace, helping us understand how plant shapes have transformed over time. During your visit, you'll have the opportunity to use 3Devo, our custom software, to build a mini-genome and observe how it governs plant growth.

This event is now fully booked. Please use this form if you wish to be added to a waiting list. You must have a valid ticket to attend this event.

Please note that this workshop is suitable for ages 12-years and older.

Can You Outpace Evolution?

Pick genes and design your own plant! How does it stack up against plants created by others?

Learn how genes interact in complex networks, and how small changes can make a big difference to the shape of plants. Discover the challenges of engineering plants, and find out if you can do better than evolution!

Design Your Own Plant

Step behind the scenes at the Sainsbury Laboratory and discover how we study plant evolution and development. Explore our workspace, use some of our research tools, and try computational modeling to create your own plant design.

Cambridge Festival background

The Cambridge Festival is a mixture of online, on-demand and in-person events covering all aspects of the world-leading research happening at the University of Cambridge. It is held every year and runs over two-weeks during March.

Sign up for Cambridge Festival updates and special features, and be the first to know about what to expect in 2025.

Past Cambridge Festival events

View the past inquiry-based experiments that we ran for the Cambridge Festival below.

Cambridge Festival 2024

Moving without Muscles — Plants as Mechanical Engineers

1.5 hour science practical science session

What visitors did

Visitors undertook inquiry-based experiments and analysed results on plant biomechanics.

Plants in motion

Time-lapse movies reveal that plants move quite a lot. You might have even observed plants moving when petals or leaves change their position between the morning and afternoon.

Plants move in response to a variety of stimuli like light and touch. The venus flytrap can move rapidly to capture its prey and sunflowers move as they track the sun through the day.

But plants don't have muscles or nerve cells. So how do they move?

Despite the lack of muscles, plants have evolved a wide range of mechanisms to generate motion.

During their visit to the Sainsbury Laboratory visitors explored various methods plants use to move - and designed experiments to understand the physiology that allows movement.

Plants and their BFFs

Members of the public joined scientists from the Sainsbury Laboratory Cambridge University (SLCU) to explore a fascinating relationship between plants and their best fungi friends (BFFs) during the 2023 Cambridge Festival.

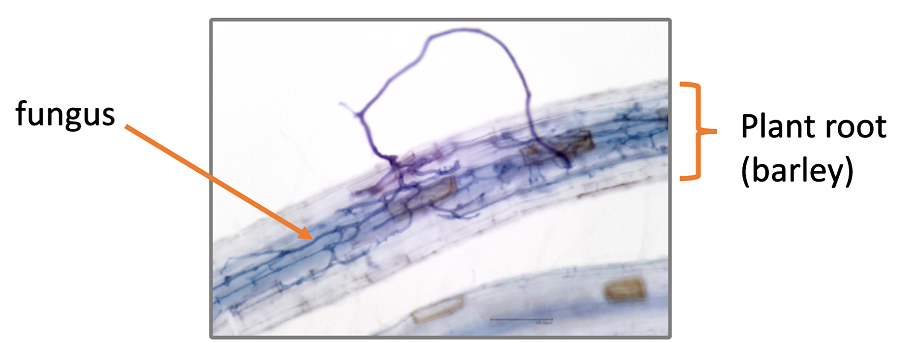

Almost all crop plants form associations with a particular type of fungi – called arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi – in the soil, which greatly expand their root surface area. This mutually beneficial interaction boosts the plant’s ability to take up nutrients that are vital for growth.

Harnessing the power of one of the Sainsbury Lab's latest discoveries that makes fungi visible, visitors were able to see with their own eyes fungi colonisation of living roots.

Visitors were also introduced to the use of scientific equipment and used a Keyence microscope to see the tiny structures fungi build inside root cells and learn about an Artificial Intelligence (AI) software program developed at SLCU to measure how much of the plant root is colonised by fungi.

Visitors also did some data analysis recording the growth of plants with different diets.

Together, visitors and scientists measured, generated data and analysed the results of experiments to see if the relationship between plants and fungi was influenced by the addition of phosphorus fertiliser.

A young visitor to the Lab measuring root-length as part of an experiment on plant-fungi relationships.

The Phosphorus dilemma

Phosphorus is one of essential minerals in fruit and vegetables that we need to build our bones, teeth and even our DNA.

We find phosphorus in the soil and plants absorb phosphorus from the soil via their roots. However, not all types of soil have phosphorus immediately available. In this case, plants can use the help of fungi to either break-down or reach out to other phosphorus sources.

Synthetic sources of Phosphorus

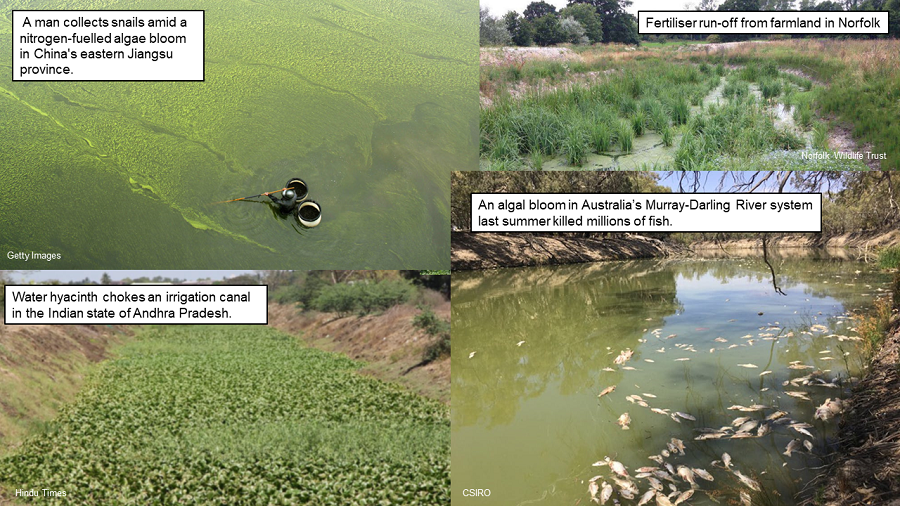

In agriculture, phosphate fertilisers are used to promote plant growth. Unfortunately, the over-use and run-off from fertilisers can cause severe environmental problems, including algal blooms.

But what are our alternatives if we want to grow healthy vegetables and crops? Can we utilise the natural interactions between plants and fungi to promote plant development?

SLCU research is trying to understand how these plant-fungi relationships form and how best to enhance these connections to reduce the need for fertiliser.

Thin Air, Plants and Food Security

Dr Nadia Radzman, who is a plant scientist at the Sainsbury Laboratory Cambridge University and Co-chair of Cambridge University Food Security Society, led a hands-on Cambridge Festival 2021 workshops exploring how some plants can make their own fertiliser out of thin air.

Visitors had the opportunity to use scientific laboratory equipment and processes, including using PCR, to identify what type of bacteria are living in specialised organs, called nodules, on the roots of white clover (a legume plant) they collected from their garden, allotment or school grounds.

Dr Radzman’s research focuses on understanding how legume plants, like peas and beans, partner with soil bacteria to produce their own nitrogen fertiliser. There is a great diversity of different naturally occurring soil bacteria that form these nitrogen-fixing nodules – some are better at fixing nitrogen than others.

It was interesting to see the diversity of bacteria we having naturally occurring in soils across our region and the UK.

Nitrogen is one of the major limiting factors for food production in developing countries where nitrogen fertiliser is unaffordable for most farmers. While in developed countries, the over-use of nitrogen fertilisers is a major problem causing pollution of waterways. Nitrogen fixing plants, like legumes, naturally feed the soil and benefit both agriculture systems. Dr Radzman’s research is looking at two ideas – how to improve and reintroduce forgotten legume crops into agriculture (increase the diversity of the crops we rely on) and how to make better legume roots (that can form interesting and beneficial structures such as tubers and nodules) using small molecules called peptides.