Humans of SLCU

Taking inspiration from Humans of New York, each week we will feature people from our SLCU community.

Meet Ray…

Dr Raymond Wightman | Imaging Core Facility Manager | LinkedIn

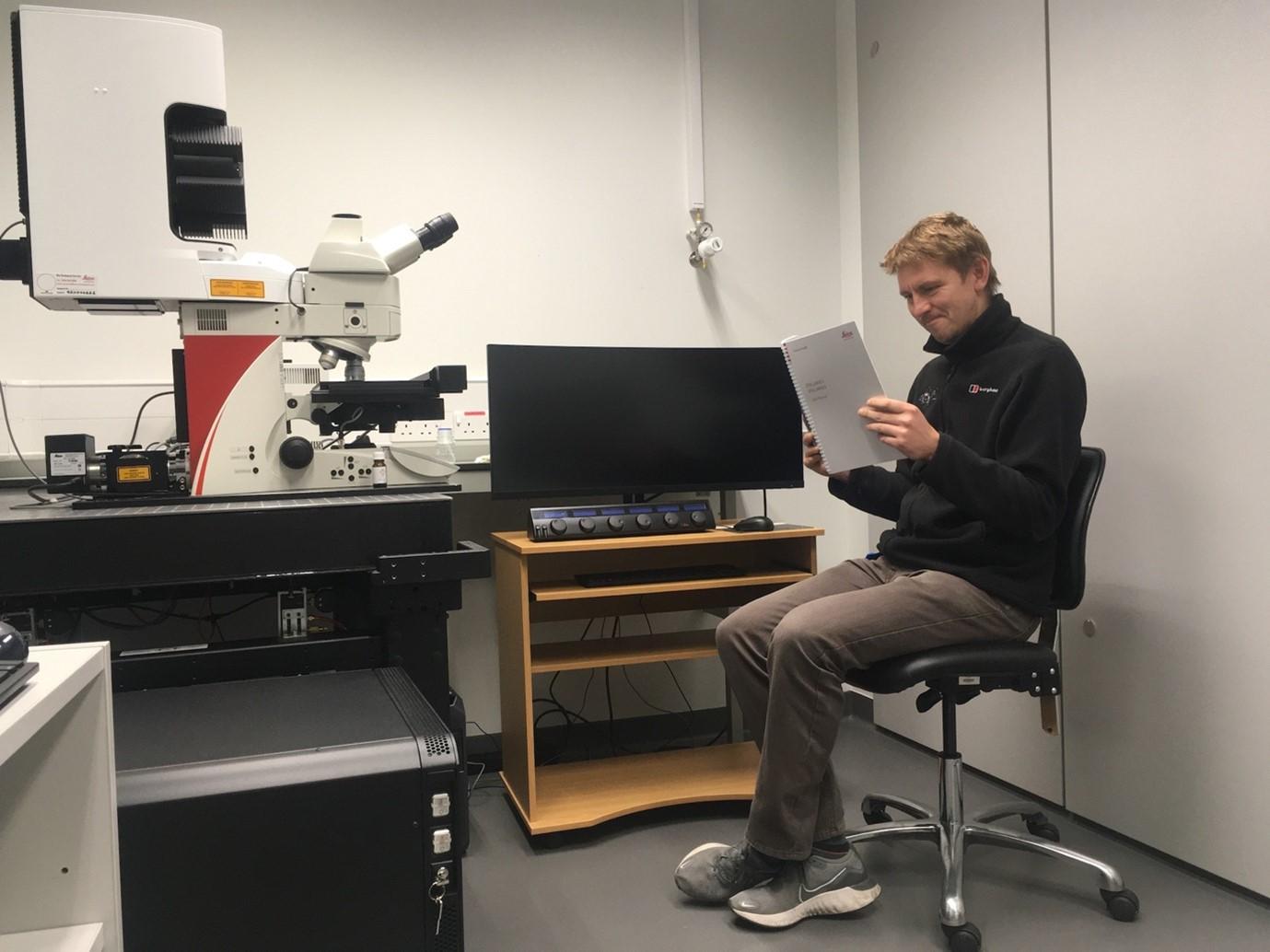

Ray joined SLCU in 2011 as a postdoc in Elliot Meyerowitz’ group working on shoot apical meristem development. Together with a small team, he now runs SLCU's microscopy facility where they train and support researchers in the use of light and electron microscopes.

Early days at SLCU

It was pretty quiet compared to today. There was about 10 researchers here when I started and we were all mixed up on benches at one end of the South wing. 90% of the building was empty. We worked around the teething issues you get with a brand new building - I remember at night you could walk down a corridor and suddenly the lights might go out. I was only supposed to be at SLCU for a short 16-month project, 12 years later I’m still here!

Before SLCU

Before SLCU I had moved a lot between posts. I did my undergraduate degree in Biochemistry at Dundee in the mid 90s and there was a big buzz when the complete genome sequence of the first eukaryote, the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was published. There are about 6000 genes in this yeast and at the time most had completely unknown functions. There was an intriguing observation that some genes were copied over and over again between the ends of the chromosome arms and I went to work on what was going on there (and why) for my PhD at Leicester. My work involved sampling yeasts from all over the world to see which genes were amplified in any given species. I also compared yeast from supermarket bottled beers. I got an allowance of beer, removed most of the contents (!!!) except the dregs in the bottom - and then I got good at resurrecting the yeast and looking at gene copy number in their DNA.

I still have all the yeast strains hiding in the freezers at SLCU. Recently they were all shared with a big project at another UK university that were looking for yeast that could cope with harsh conditions for industrial uses.

After my PhD I kept with yeast and, as a Sheffield postdoc, I worked on the human pathogen, Candida albicans. This is where I first started doing proper microscopy. By the time I left, for whatever reason, yeast research jobs had dried up and people instead were going crazy over the completed genome sequence of this weed called Arabidopsis thaliana – so I went to Manchester and worked on my first laser scanning confocal microscope. My main project was to find a way of seeing some cellular machinery in a hard-to-see cell type as it spins out the cellulose for wood formation. That was 2003. It took me 20 years to actually do this. This taught me that science can take absolutely ages.

Plant adventures in the Spanish Pyrenees

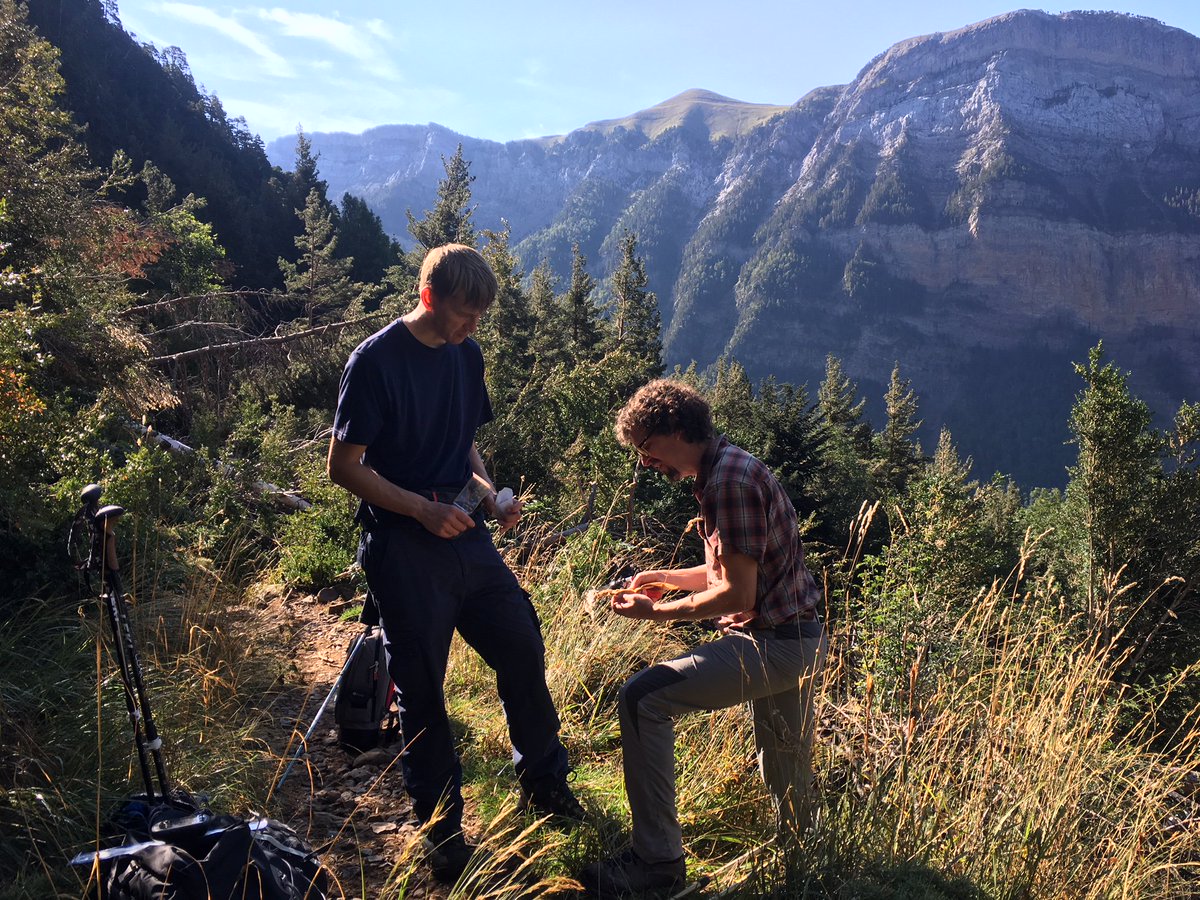

I dragged one of the microscopes to the Spanish Pyrenees on a trip with the garden staff and took microscopy images at the foot of mountains and in my hotel room. We studied a species of Saxifraga where on one side of the Pyrenees its leaf phyllotaxis was opposite, the other side it was spiral (photo below) and where they met in the middle the same plant would switch between opposite and spiral. We brought some back to the Botanic Garden for further study but the hot Cambridge weather killed most of the plants.

Raymond Wightman and CUBG's Simon Wallis collecting Saxifraga plants on the side of a hillside in the Spanish Pyrenees.

A Saxifraga species collected from the Spanish Pyrenees where on one side of the Pyrenees its leaf phyllotaxis was opposite, the other side it was spiral (photo above) and where the plants met in the middle the same plant would switch between opposite and spiral.

An average day

Now I work with a small team that runs the microscopy facility. We train and support researchers any way we can to use the vast array of light and electron microscopes to help with their work. I do still dabble in research as it helps me keep my own training up to date. The facility has a very good relationship with the botanic garden and we have used the microscopes to discover pretty amazing things about plants that I never knew existed before this job. A few years ago we discovered a very rare mineral, vaterite, on a small group of alpine plants that were sitting in the garden. It was great to see the Wikipedia entry change as a result of this work (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaterite ).

It’s always varied. I like being close to the microscopes but there is a lot of other duties in a large facility such as making financial, maintenance and purchasing decisions. For example - a typical confocal microscope costs £300,000 to purchase and £20,000 per year to run and might need several engineer visits, remote diagnostics and new parts. The lab has ten of these confocals.

Q&A with Ray

What is your favourite tool of the trade ?

I have a pair of super-sharp tweezers for dissecting shoot meristems.

What do you wish you knew when you were first starting off your PhD?

That everything takes far far longer than you expect it to.

Do you have a favourite song?

I sometimes spend long hours on the cryoSEM and, with no windows in microscopy, I often listen to music or the radio to keep me sane. I like cryo-inspired music like “Cold as Ice” by Foreigner and “Ice Ice Baby” by Vanilla Ice. When I’m in a dark room on the confocal microscopes I often listen to “I can see clearly now (the rain has gone)”.

What is something that most people don’t know about you ?

I passed my tractor driving test at age 16 which allowed me to drive tractors on the public roads and even dual carriageways. I spent most summers on a tractor and even had A-level revision notes in the cab just before my exams.

If you were a plant, what plant would you be and why?

Hops (Humulus lupulus). It’s the most important organism in the world after Saccharomyces cerevisae.