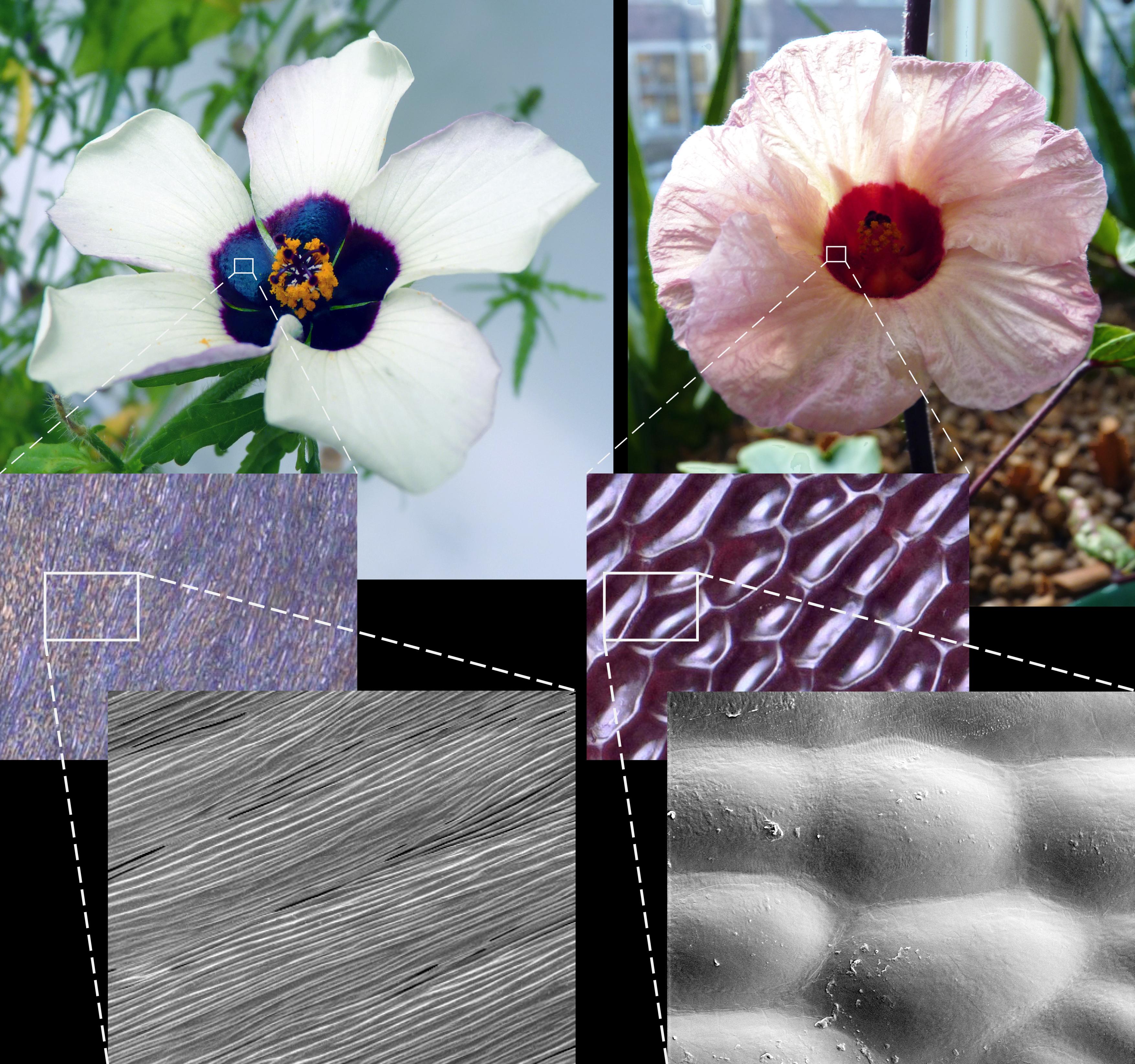

There is a clear visible difference between striated and smooth petal surfaces when the petals are viewed under microscopes: Hibiscus trionum (left) has microscopic ridges on its petal surface that act as diffraction gratings to reflect light, while Hibiscus sabdariffa (right) has a smooth surface.

Cambridge researchers have shown that plants can regulate the chemistry of their petal surface to create iridescent signals visible to bees.

This project revealed that there is a combination of processes working together and allowing plants to shape their surfaces. Dr Moyroud added: “Plants are formidable chemists and these results illustrate how they can precisely tune the chemistry of their cuticle to produce different textures across their petals. Patterns formed at the microscopic scale can fulfil a range of functions, from communication with pollinators to defence against herbivores or pathogens. They are striking examples of evolutionary diversification and by combining experiments and computational modelling we are starting to understand a little bit better how plants can fabricate them.”

“These insights are also useful for biodiversity and conservation work because they help to explain how plants interact with their environment,” said Professor Glover, who is also Director of the Cambridge University Botanic Garden, in which the researchers first noticed the iridescent flowers of Venice mallow. “For example, species that are closely related but that grow in different geographic regions can have very different petal patterns. Understanding why petal pattering varies and how this might affect the relationship between the plants and their pollinators could help to better inform policies in future management of environmental systems and conservation of biodiversity.”

Investigating what drives 3D petal patterningThe researchers took a stepwise approach to the investigations. They first observed petal development and noticed that the cuticle patterns appear when cells elongate, suggesting that growth was important. They then determined whether measuring physical parameters related to growth, such as cell expansion and cuticle thickness, could adequately predict the patterns observed, and found that they couldn’t. They then took a step backwards to try to identify what was missing. The properties of a material, whether inorganic or produced by living cells like the cuticle, are likely to depend on the chemical nature of this material. With this in mind, the researchers decided to look at cuticle chemistry, and found that, indeed, this is a controlling factor. To do this, they first used a new method from the chemistry field to analyse the composition of the cuticle at very specific points across the petal. This showed that petal regions with contrasting textures (smooth or striated) also differ in the chemistry of their surface. Comparing with smooth cuticle, they found the striated cuticle has high levels of dihydroxy-palmitic acid and waxes and low levels of phenolic compounds. To test if cuticle chemistry was indeed important, they then pioneered a transgenic approach in Hibiscus to alter cuticle chemistry directly in the plants, using genes similar to those known to control the production of cuticle molecules in a different model plant, Arabidopsis. This showed that cuticle texture can be modified, without changing cell growth, simply by modifying cuticle composition. How can cuticle chemistry control its 3D folding? The researchers think that a change in cuticle chemistry affects the mechanical properties of the cuticle as, even when stretched using a special device, transgenic petals with smooth cuticle remained smooth, unlike those from wild-type plants. |